The Inner issues of

Painting Vs the Outer, Circumstantial Issues

Ben Lau MFA

Introduction

I have always wanted to examine the issues of interpretation, fetishism and gender- issues claimed by art historians and critics alike as significant elements in any work of art. The purpose of that is to see how research in that direction may yield something useful pertaining to a better understanding of art. However, I always think that a full understanding of a work of art must be attained through an examination at its core, that is, the art’s own reason for being, NOT by proving its relevance to outer issues which reside at the circumference of art. Of course, I am referring to that specific kind of art that steadfastly refuses to be governed under the jurisdictions of those outer issues.

A work of art’s reason for being can be found within the internal considerations of that art regarding its potency as an agent of communication, such as its structure, balance, movement, composition, inventiveness and its metaphors. Those are the inner issues of a work of art as compared to the outer ones. In other words, the reason for the art’s being lies in the consideration of those inner issues- enduring factors that may or may not provide beauty, sensuality and harmony. Those internal issues, if understood intuitively and approached appropriately, forms the core of that art. The issues of interpretation, fetishism and gender concern only with the external and circumstantial effects of that art. They have attracted attention only because of the art’s presence on the art historians’ radar of time and space.

Since contemporary discourses and critiques have placed such an extraordinarily high value on those external issues, I shall examine the New York master, Knox Martin’s works in the light of their relevance within the cultural context of the contemporary world. Eventually, I shall be able to compare such discourses with Knox Martin’s own criteria about his art in order to reap a greater clarity of vision for the viewers.

A brief biography of Knox Martin

Knox Martin was already famous in the 50s- before his protégé, Robert Rauschenberg even became an artist. He was represented by Charles Egan in the 50s sharing the same galleries with such heavy weights as de Kooning and others. He is well respected and has been thought of as an artist’s artist by contemporary artists, art historians, and critics alike. According to Edward Leffingwell, Knox Martin has an “extensive exhibition history beginning with Stable Gallery in 1953.” ( Edward Leffingwell December Art In America).

I have chosen the art of Master Knox Martin to be the subject of my study because he proclaims his own works as heir to the tradition of painting represented by Picasso, Matisse, and de Kooning.”( www.knoxmartin.com). To be heir to such a tradition generates particular interest because many of the issues in the postmodern world can be understood in terms of their theoretical opposition to such a tradition.

Interpretation

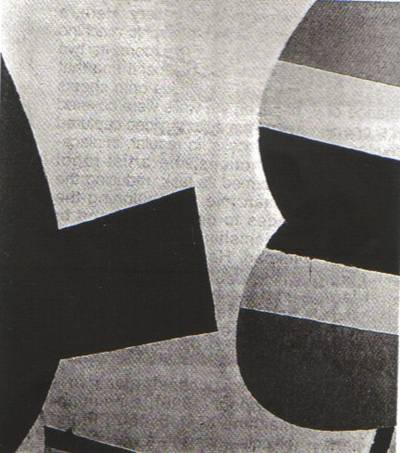

Figure 1: Knox Martin Caraha! Magna on Canvas 1968

Figure 1 shows Knox Martin’s Caraha! ,a painting of magna on canvas in 1968. It was the painting shown at Janos Gat Gallery in New York City in the Fall of 2001. According to Jonathan Goodman, it is “a large, sensuous work that can be read in both figurative and abstract terms.” However, I think this painting can only be read figuratively since the Knox Martin I am familiar with has never painted abstract art, if “abstract” means “non-figurative.” This is a very important point of clarification since one should not point to a deer and say, “That is a dog!” The structure on the left represents the erect phallus and it boldly enunciates the painting’s erotic status. On the right are two breast-like forms painted in orange, white and blue stripes. Goodman said, “For all its abstraction, Caraha! is clearly meant as a deeply erotic presentation of male and female forms.” (September 2001 Art in America). That assessment is a contradiction in terms because with “abstraction” (generally understood to mean “paintings that do not deal with the representations of reality), we cannot yield “figurative!” And if it is “non-figurative,” how can there be “an erotic presentation of male and female forms?” Looking at this painting while retaining the fond memory of Knox Martin’s vast oeuvre in my mind, I can explain why it is a simple matter to decipher its meaning and to know the exact intent of the artist. The fact is that the Knox Martin I know has adopted the woman theme extensively in the vast majority of his paintings and erotica is his perennial, even lifelong subject matter.

Contemporary art critics and historians alike have assigned an important place to the interpretation of a work of art. According to Umberto Eco, the sign is a gesture produced with the intention of communicating (Eco 25). In Knox Martin’s work, the viewer receives his signs of deeply erotic connotations and the artist’s intention to communicate something erotic is therefore quite conspicuous. Umberto Eco thinks the sign is also revelatory of a contact, in a way that tells us something about the shape of the imprinter (Eco 27). In this case, the contacts are geometric forms as well as erotic forms. Umberto Eco also elaborated that texts generate, or are capable of generating, multiple (and ultimately infinite) readings and interpretations (Eco 43). In the interpretation of Knox Martin’s painting, that “text” is not a verbal one, it is a text in the form of iconography. That “text” takes the erotic forms of the phallus and breasts. In the context of Knox Martin’s usual subject matters my interpretation is predictable, reliable, and concise. This assessment of stability is at loggerhead with Eco’s claim of “infinite readings and instability of meanings.” The interpretation for Knox Martin’s works is as stable as the consistency in his art, because, firstly, Knox had pointed out in a recent interview with me ( Knox was my painting teacher at the Art Students League) that every single one of his canvases is figurative and representational (that is to say, he has never produced abstraction and has never been interested by abstraction) Secondly, his declared goal in bringing out the sensuality and voluptuousness of the transfigured female form directly point to a predictable, stable and constant artistic intent of erotica. Lastly, the meaning of his themes is only of secondary or circumstantial importance because Knox Martin, like Picasso, treats the subject matter as “an excuse for painting (Huffington 130).” Knox Martin even goes beyond that: on his website he speaks of painting itself as his subject matter!

According to Umberto Eco, “without the fluidity of meanings, what we call metaphors would be equivalent simply to say that something is something. But metaphors say that one thing is at the same time something else (Umberto Eco 40).” It appears that contemporary art critics follow this line of thinking quite often regarding interpretation and they revel in “the fluidity of meaning and the multiple readings of metaphors.” Interpretation, after all, is the stage craft of critique and it provides an incentive for an infinite number of readings, thereby keeping the readers of art criticism entertained. But entertainment does not require clarity or understanding. Neither does Arthur Danto’s statement about the works of Knox Martin bring us anywhere closer to that clarity. In his “Adventures in Pictorial Reason” (Danto /articles/ www.knoxmartin.com), Danto claims that Knox Martin’s works evoke “the circus” and they “remind” him of Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup. If comparing real Art to “Pop Art” is a way of entertaining his readers, it is a most uninformed way indeed! And with all his prestige as a renowned art critic, Mr. Danto never has the need to revisit his fallacies and examine his poor judgment!

As I have said before, interpretation has never been a central issue with Knox Martin, as virtually all of his paintings, which are geared toward a singular, erotic reading, attest. The art critic’s blind- men- feel-the- elephant- sort of interpretations only serve to muddy the water further.

Another critic Julio Congora, obviously in deference to Danto, wrote in the Janos Gat Gallery catalogue: “In Arthur Danto’s essay on Knox Martin, Adventures in Pictorial Reason, Martin’s stripes and circles are ‘striped tents, loudly patterned costumes of clowns.’ Let us also include flamenco dress, polka dots, the contrasted black and white of the male Spanish dancer.” ( Congora 2)

At the same time, Congora concluded his essay on Knox Martin by asking: “What is the promise? What are the antipodes of the knowable?” His answer to that question: “A basic intuition, displaying the shadows of creation at their most elemental!( Congora 2)” Here, Congora and Danto’s readings of the metaphors suggests everything from clowns to flamenco dress and polka dots to Spanish dancer, even to Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup! In my opinion, precisely none of those interpretations has anything to do with a “basic intuition, displaying the shadows of creation at their most elemental!” (Congora 2) On the other hand, understanding the metaphors in terms of a singular and stable erotic intention can point us in that direction. It is the appropriate interpretation if we want “a basic intuition, displaying the shadows of creation at their most elemental!”( Congora 2) as Congora’s own statement attests. With the proper approach the promise of a communion with Knox Martin’s art can be realized.

Knox Martin himself, regarding his Black and White exhibition at Janos Gat Gallery said in 2001 said, “These Black and Whites are about creation and, for the most part, women and flowers. Under the new science, woman is cousin to plants; women are mobile plants (Congora 3). Knox continued to say, “Cezanne, writing about Tintoretto: He worked in black and white and red. I know what that is. Colors are painful.” (Congora3) One can feel his powerful erotic intent in a statement like that. By referring to women as plants, he extends his eroticism to everything he touches. What is sexy is neither women nor plants but his artistic touch. By stressing the importance of black and white, he brings our focus back to the form, as the pure form has no color.

What I have tried to point out is that art critics are mostly concerned with the external or circumstantial aspects of a work of art while the artist himself is mainly concerned with the internal aspects of his own production. This issue of interpretation only represents one of the many theoretical conflicts between the artist and the art historian. It shows that each party has different interests as well as opposite agendas when looking at the same work. As a third party, I must admit that I am biased towards the artist’s opinion over that of the art historians. The reason is never convoluted: the artist is the creator of his work and he is therefore a better spokesman regarding its interpretation.

Fetishism

Charles de Brosses said that fetish is the worship of material objects originated from the primordial psyche for the individual to derive an inexplicable comfort or pleasure for such a fixation (Nelson/shiff 307). Louis Althusser appropriated the Lacanian theory, claiming that because of the split ego, an alleged development in the infant’s mirror stage, the fetishist misrecognizes his socially constructed persona as his true self (Nelson/ Shiff 315). Luce Irigaray and Julia Kristeva (Nelson/Shiff 315) held feminist views and their reading of fetishism cannot depart from their own aversion against a phallo-centric, patriarchal construction. Without exception, the contemporary art critics and writers have found fetish to be an extremely undesirable thing that confuses the split ego to fix on as a kind of comfort-yielding substitute, psychologically speaking. Fetish, according to those writers, does not just construe guilt but is also something that needs to be actively avoided in order to make inroads for the “enlightened” re-development of culture in a society.

The Enlightenment theory of fetishism decries fetishism as an idiosyncratic worship that cannot distinguish between subjective desire and objective causality. In this light, Immanuel Kant’s observation can be expected to provide a “clear” solution to the problem of fetishism. In Kant’s essay, Critique of Judgment (1790), Kant noted that the aesthetic faculty of a self-critical mind is one that is capable of distinguishing within sensuous experience between the purposive-ness of its own subjectivity and the objective purpose found in teleological systems such as biological organisms. In other words, Kant was saying that because of the debased quality of fetishism, i.e. one that is not worthy of a critical mind- an enlightened subject must be able to distinguish the aesthetic of the beautiful from that of the ugly.

Figure 2: Knox Martin Woman 2001

In Figure 2, the face of the woman occupies much of the upper left quadrant of the painting with a pair of very prominent eyes. The right ear is partially covered by a set of powerful calligraphic lines denoting the woman’s hair. The slanting nostrils pay tribute to a pair of breasts which are planted obliquely orienting toward the north-western corner in the painting. They are in much smaller proportion than the face and they take on the strange forms of cucumbers. Such a depiction is both erotic and inventive. The rest of the painting depicts the woman’s buttock, legs and other parts of her body including her organ (possibly to the left of the artist’s signature). Knox always remembers to place the organ in the majority of his paintings entitled “woman” so this one should not be an exception. The visual movements offered by powerful calligraphic lines delightfully forming the flowing cress are framed within a vast oval form, counterbalancing the firm white thigh oriented toward the northeast direction, and if connected to the nose, an S structure in the composition takes shape and looms large.

Figure

3: Zaire wood carving Figure 4: African Art

Figure 5: Matisse The Blue Nude

1952

Figure

3: Zaire wood carving Figure 4: African Art

Figure 5: Matisse The Blue Nude

1952

The painterly rearrangement of the various parts of the bodies, their depiction in exaggerated proportions and the way in which the metaphors are posited within powerful, calligraphic lines suggest a primitive style, which in turns implies “fetishism.” After all the visual representations from figure 2 through 5 have been carefully examined, it is not difficult to see the tribute Knox Martin pays to African art for its primitive, wildly sensuous, but pristinely geometric attributes.

To the uninitiated, the Zaire wood carving takes on a “bizarre” look, suggestive of a “fetishist” kind: the elephantine ears, the huge conical breasts, the limbs that look like bamboo trunks, the drooping inner labia of the vagina and everything else about the figure serve to “subvert” the Renaissance norm of Classicism. To eyes little accustomed to African art, the statue could even assume an aspect of “ugliness!” Figure 4 through 6 similarly suggest primitivism and “fetishism.” It may be true that African art does not conform to the usual norm of beauty in the West, yet if one looks at them with rapt attentions, an exotic kind of beauty slowly comes through.

In Figure 4, for example, the African carving of a mother antelope and her piggy-backing offspring takes on a dignified magnitude of transcendental and sensual beauty. The extremely sensuous forms and the space in between those forms suggests an uncanny geometric groundwork in the composition. The same can be said about Matisse’s Blue Nude in Figure 6, where the forms and the space in between are woven into an enduring composition. As we size these works of art up (figure 2 through 5) for the sake of comparing, it is not difficult to note Knox Martin’s allegiance towards primitive African art. If there is the evidence of a geometric groundwork (as in Classical Greek sculptures) responsible for timeless beauty and if such beauty can be felt throughout these works of art (figure 2 through 5), then the claim that fetishism is the aesthetic of the ugly is plainly unfounded and not worthy of further contemplation.

In my MFA Graduate Thesis paper, I have attributed the essence of my works to a design principle grounded in mathematical relationships that promote timeless beauty. My aesthetic is therefore one that dismisses the cultural border in art and diminishes the effect of existential relativity. Hence there is to be neither a European nor an African styled- beauty. There is only beauty! Just as one cannot describe mathematics as hermeneutical or fetishist, an art based on mathematical relationships as a ground-plan for the expression of beauty has none of that in its purity and serenity. That kind of beauty, noted by Knox Martin in his essay in the 2001 Black and White Exhibition catalogue at the Janos Gat Galllery, is something that causes in us “an awakening beyond reservation!”

In the same essay, Knox Martin also noted, “All great works made its appearance, the poems, sculpture, paintings, music, were presented crystal clear and the nonessentials fell away.” (Congora 3). What are the nonessentials? They are those elements that are not found at the core of the work. They are called nonessential because they only refer to the work circumstantially.

Gender

According to Whitney Davis, representation is always gendered and gender is, to adopt Foucault’s thesis, a social construction (Nelson and Shiff 332). The important thing, he said, regarding the gender aspect of a representation, is “gender agreement rather than gender difference” because agreement governs difference. He also said, “ Any depictions of women and of things or environments are bound and governed by the gender with which they must all contextually agree, namely, the male inflection spread through the enunciation (Nelson and Shiff 331).” He stresses the importance in the gendering of a representation by saying, “To insist that gendering is the constitution, interrelation, and transformation of agreement classes is not only to observe how social interests, distinctions, and hierarchies in the designation of sex difference are carried through representation.” He claims that the marking of difference cannot be seen outside of the thematic agreement. He said, “The marking of gender difference depends on and can generate an extensive and complex systematicity through agreement.” ( Nelson/ Shiff 338) As a result of this agreement and inflection, even the objects normally regarded as neutral, such as the hills and the trees, also take on their various genders.

Looking at just two paintings of Degas, Whitney Davis has already felt an urge to make the claim that he is able to identify certain gendering traits inherent in Degas’ painting (he shows two versions of Degas’ Young Spartans.) Those traits, according to Davis, are: misogyny, feminism, fetishism, pedophilia, and homoeroticism (Nelson /Shiff 340). Having said this, I presume he would imply that Degas is found guilty of all that! My critique of Whitney Davis’s observation is, even without faulting him for his pretension of authority in predicating his views on a purely external, existential and circumstantial conjecture about Degas’ painting, is that he is simply too ready to make assumptions as evidenced in many of his views. As a result, he tended to construct his thesis of gender in representations on mostly faulty and self-deceptive premises. I will adopt Knox Martin’s 2003 drawing to prove this point.

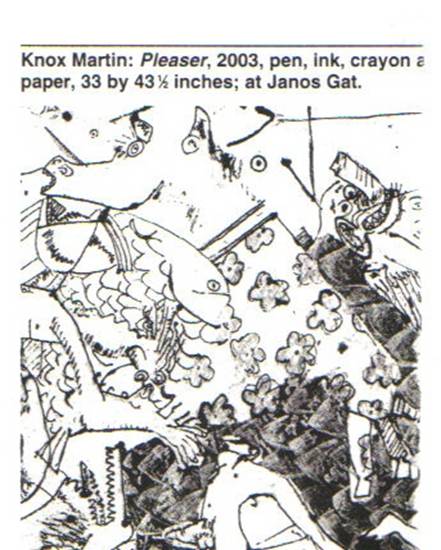

Figure 6: Knox Martin Pleaser 2003 (detail)

Figure 5 shows the detail of the 2003 drawing on paper of Knox Martin, Pleaser. It was exhibited at the Janos Gat Gallery that year in New York City. In an article written in Art in America regarding this group of drawings, Edward Leffingwell said, “There is substantial whimsy to Martin’s recent phantasmagoria of animal and human forms.”

Leffingwell also noted that Knox Martin has taken an unexpected turn into an irrational world of lust and vanity and that grotesques disport on the relatively open, glittering gold field of Pleaser. In the drawing, an aroused male nude at the edge of the lower left quadrant bows his back in orgasm in the general direction of creatures that resemble a alligator and a bird. A horse dressed in a hide of blue flowers cavort across the drawing’s field. Leffingwell further noted that “Martin takes pleasure in his images and process, in the authority of his draftsmanship and the incisive nature of his wit, and with the simplest of mediums he invests these teeming bestiaries with the life of dreams.” ( Art in America December 2003)

However, Leffingwell also mentioned that this new work comes as a surprise to those who have long associated Martin with resolutely geometric, brightly colored abstractions, familiar to millions of New Yorkers through the vast, intersecting geometries of massive public wall paintings. To a viewer familiar with the long artistic career of Knox Martin like me, this set of new works is fully consistent with his usual operation of design within the framework of a geometric ground plan, and hence this work, Pleaser, is by no means surprising in that respect. What is truly surprising is the outpouring of curious forms and exotic associations in Knox Martin’s production. His imagination is both wondrous and inspiring considering the fact that the artist has celebrated his 82nd birthday last February. But with an astonishing I.Q. of 196, that does not surprise me at all!

Now let us return to the geometric core of his art in this drawing. As we can see, the line separating the horse-looking creature from the dog-looking one is straight and resolute. The darkly shaded area, if connected and taken in at one glance, suggests beautiful Oriental calligraphy writ large. The composition is resplendent with circles and rectangles, weaving the various forms of animals and humans into an extremely rich orgy of painterly narrative and the exotic fabric of a fable. The work is compact, powerful and transforming. In other words, Knox Martin has never abandoned his regular mode of creative operation. As an artist paying tribute to the art of Cezanne and Picasso, he is persistently working out the mathematical relationships in his composition in the same way as Matisse with his Blue Nude III.

Were Whitney Davis to look at this Knox Martin drawing, with the former’s emphasis on the need to determine the gender of representation, he would probably think of the art as assuming the gender of the heterosexual male because the images in it invoke the phantasm peculiar to the sexuality of a heterosexual male. Without dealing into the inner working of the art, which is at the core of creation, Whitney Davis has failed to explain the reason for the art’s being with that assessment- nothing more than a circumstantial speculation. To speculate on the gender of a painting cannot lead us anywhere beyond a mere inconsequent chattering about the status of the art being one of male heterosexual. It has preciously nothing to do with the potency of the art as a powerful vehicle of erotic, sensuous, geometric form of communication. In other words, Whitney Davis has failed to see the true Degas. Mr. Davis can only pick up the crumbs fell from the extravagant banquet offered by Master Degas and may he enjoy such beggary! Such a speculation by an established art critic can only lead an art student farther and farther astray and the central question of “what makes this thing tick?” can never come to its justified conclusion.

Conclusion

The issues of interpretation, fetishism and gender are issues posited at the circumference of a work of art. Arguably, they may be important points to contend with because such contemplations provide a frame of relevance for the art historians in the description of an artist’s work in the contemporary cultural context. However, I think that such contemplations are idol because any discourse of those issues can only be an outside, circumstantial depiction of that art, and it does not allow the art student a chance to visit the core of art. In order to find out about a work’s reason for being, one must examine art at its root. A tunnel vision on art is detrimental to its understanding. Instead, one must look at the big picture with the broad vision capable of scanning greatness and timeless beauty from past civilizations. The consideration of inner issues inherent in a work of art is a reliable strategy in determining an art’s calling, or its reason for being. It is vital in providing an explanation of why the work can be so enticing and engaging. In other words, to understand what makes the thing tick, one must examine it at its fundamental. Through looking at Knox Martin’s work, it is possible for the viewers to “trim away the nonessentials” (Congora 3) to finally arrive at the inner core in a work of art. The long career of this venerable artistic genius indicates that he has consistently created his art from an underlying geometric ground plan of design, the mathematical relationships of which point to the notion of sensual, sublime and transcendental beauty.